Our commitment to evidence-based research

As part of our strategy to reimagine, redesign and rebuild the criminal justice system, we are committed to strengthening our connections with universities, research bodies, and academics. This ensures our work is firmly grounded in evidence-based research.

Each year, we seek to partner with a university to hold a research symposium to explore a different pillar of our vision for a fair and effective criminal justice system: one that is Safe, Smart, Person-Centred, Restorative and Trusted. Following each symposium, we will compile a comprehensive compendium encapsulating the insights gained.

In 2023, in partnership with the University of Westminster, we held our first symposium on the theme of improving trust in the criminal justice system. We also launched a new category of membership for individual academics (Masters level and above) to strengthen these connections.

Our second symposium will be held in Autumn 2024 on the theme of a safe criminal justice system.

Click here to become an academic memberInaugural research symposium: How can we improve trust in the criminal justice system?

On 3 March 2023, the CJA, along with our partner, University of Westminster, held our first research symposium on the theme of improving trust in the criminal justice system and research. Over 100 delegates attended, including academics, voluntary sector practitioners, statutory bodies, campaigners, people with lived experience and students from across the UK.

Compendium 1: How can we improve trust in the criminal justice system?

Event overview

In March, the Criminal Justice Alliance (CJA) partnered with the University of Westminster to bring together CJA members and partners with academics to convene our inaugural annual research symposium. At this event, we considered the theme of a Trusted criminal justice system.

We sought to create a space for academics who want to see a fairer and more effective criminal justice system to share a diverse range of research to inform our collective understanding of trust in the criminal justice system. The day was designed with the explicit intention of hearing different perspectives of what trust might mean in the criminal justice context, breaking down boundaries and encouraging collaboration, conscious of the silos that exist across different parts of the criminal justice system-between policy, practice, research and lived experience, between the voluntary and statutory sectors and between people in different geographical regions. Over one hundred delegates attended, including academics, voluntary sector practitioners, statutory bodies, campaigners, people with lived experience and students from across the country.

Some of the questions we considered during the day were:

- How do we measure trust and confidence in the CJS?

- What helps or hinders the trust of different groups involved with and impacted by the CJS?

- What does trust in the CJS look like through race- and gender-sensitive lenses?

- How do we build public trust in a less punitive CJS?

- What role does trust play in criminal justice leadership and management structures to achieve cultural change?

- How can we improve trust and transparency in policy and decision-making processes in the CJS?

- What is the impact of digital technology on trust in the CJS?

- How can we promote greater trust in criminological research, for example through more creative, participatory and peer-led methods?

- How does trust link to the quality of research evidence and the credibility of messengers, including whose voices are heard, how those voices are heard and what influence they have?

Key discussions

During two morning panel discussions speakers were invited to address questions and pose provocations around the topics of trust in the criminal justice system, trust in research, the measurement of trust over time and what factors build or destroy trust. In addition to addressing questions to the speakers, participants were encouraged to interact with each other about the provocations and to share their thoughts collectively using Mentimeter polling.

We heard from:

- Joe Baden OBE, Goldsmiths Open Book Project

- Donna Murray-Turner, Another Night of Sisterhood

- Professor Mary Corcoran, Keele University

- Beth Weaver, University of Strathclyde

- Professor Nick Hardwick CBE, Royal Holloway

- Tamar Dinisman, Victim Support

- Paula Harriott, Prison Reform Trust

- Professor Ben Bradford, University College London

- Phil Hodgson, Sentencing Council for England and Wales

- Hindpal Singh Bhui, HM Inspectorate of Prisons

- Baljit Ubhey, Crown Prosecution Service

- Nadine Smith and Karene Taylor, Leaders Unlocked

Over lunch, participants had the opportunity to view a photo voice exhibition by Dr Wendy Fitzgibbons and research posters. Photo voice methodology was also used as part of the event. Participants were invited to take a photograph to show what trust meant to them (in the criminal justice system or research) to share with colleagues at the end of the day.

During the afternoon a series of workshops were convened focused on seven themes:

- Public trust

- Trusted relationships and practices

- Trusted spaces

- Risk versus trust

- Trusted research

- Inequality and mistrust

- The reach of the criminal justice system

Researchers were asked to deliver their learning in creative, imaginative, and interactive ways, either in terms of the methodologies used or the means of illuminating the findings to participants. PowerPoint slides were banned!

A system-mapping workshop spanned the rest of the afternoon, encouraging participants to visually map trust (and mistrust) in the criminal justice system and to explore the connections and relationships between parts of the system using the Three Horizons Framework. Discussion centred around what destroys trust, what builds trust and what opportunities might exist to build trust and re-imagine a trusted CJS.

Morning plenary discussions

We welcomed ten speakers to address questions and pose provocations around the topics of trust in the criminal justice system as well as confidence and trust in academic research.

Trusted research

How do we gain trust? At Goldsmiths Open Book for the Zahid Mubarek Inquiry, we had focus groups run by our Open Book students, who reflected the histories of the participants. This lessened the mistrust from the outset, but of course not totally. The problem we’ve got however, those with the backgrounds we are talking about, are still massively underrepresented in our universities.’

Joe Baden OBE, the Founder of The Open Book Project at Goldsmiths University

Joe spoke of the need for researchers to be authentic and address the power imbalance between researchers and participants; the responsibility to use research to affect change and the importance of widening access to academia.

Policing

Donna Murray-Turner, who sits on the Metropolitan Police Commissioner’s Turnaround Board, shared her experiences advocating for Black communities around policing in South London. She posed the question ‘why should we trust the criminal justice system?’ and detailed the reasons for the ‘endemic lack of trust’.

She described the recent focus on policing and misogyny hitting the headlines as it is now impacting white women:

‘On behalf of Black people, we are relieved. The things we have been calling out as mistreatment within the CJS have all of a sudden meant everyone is agreeing because they have experienced it. It’s not just us talking about stop and search and use of force on us, it’s now affecting middle class white women who just want to go about their business.’

She went on to describe how this is compounded by the lack of social support structures and services which mean communities are essentially supporting themselves, adding to the lack of trust:

‘We have to stay in the communities where our trauma is reoccurring. The system does not work for us. So, if it is not working for us, then let’s talk about how we break it down and turn it around, so women everywhere won’t take five years to get justice over a rape. So that people of colour can get the same justice as their white counterparts, so that Black children feel safe approaching a police officer without the fear that they will be profiled and treated, not as a victim, but as a perpetrator.’

Prisons

Professor Nick Hardwick (former Chief Inspector of Prisons) detailed the emerging ‘car crash’ facing the Prison Service – with estimated prison numbers over the coming years expected to outstrip prison places, combined with a system unwilling or unable to wean itself off the notion that harsher sentencing will make our society safer.

‘The long-term prison projection by 2027 is 94K and at top end of scale is 103k. There is absolutely no way that they can recruit the staff to provide the services that are necessary to manage that size of population, so there is a car crash coming. [..] What’s driving that increase? First an increase in police numbers, also the fact of giving longer and longer sentences for more serious offences. What is driving that demand to give longer sentences? I would argue it is a lack of trust. It is a lack of trust in the system. If we don’t trust the system to join up, if we don’t trust the system to treat people with respect, then you are left to fall back on lock ‘em up for longer and longer.’

Prof. Hardwick went on to propose that this ‘catastrophic, but understandable breakdown of trust in the CJS has created the conditions for the injustice and penal populism, which is driving the increase in the prison population, that will actually make us less safe.’

Victims

Dr Tamar Dinisman from Victim Support outlined why a broken system in relation to victims can result in a lack of trust. In particular, she highlighted a lack of trust in reporting rape:

‘Would you advise a friend to report a rape to the police? Only 40% of crimes are reported and one reason is lack of trust in criminal justice system. Overall justice outcomes of reported crimes are 7%. If we look at rape, only 1.7% of all reported rapes reached a justice outcome last year. Half of victims of rape who reported it decided not to go ahead with process.’

She also detailed other ways in which trust is broken, including poor police treatment of victims; the lack of firewall for victims with insecure immigration status and lack of language support meaning victims do not receive the entitlements under the Victims Code, and the long wait for justice with some victims waiting up to five years for a court hearing:

‘Good treatment is first to be believed and second to be treated with respect, and that their experience will be validated. However, we know victims of domestic abuse and rape do not get this kind of treatment and victims from minority communities and minority groups don’t get this kind of treatment. In the victim’s code, there is a set of entitlements, however we know many victims do not receive this level of support.’

Professors Mary Corcoran (University of Keele) and Beth Weaver (University of Strathclyde) provided pre-recorded engaging sessions offering their perspectives on trust related to community and probation.

Watch Mary’s session:

Watch Beth’s session:

To encourage interaction, audience members were asked to talk to those around them to reflect on the panel, considering how relevant the speakers’ thoughts were to their work and how they responded to the provocations. To wrap up each plenary, participants were asked to respond to the various provocations posed by members of the panel using online polling.

Trusted research

Paula Harriott (Prison Reform Trust) gave a passionate talk on the need to involve people with lived experience in any process to rebuild trust in the criminal justice system. She asked:

‘How is knowledge produced? Who controls knowledge production? Whose knowledge matters? Who controls who hears our knowledge? Who writes about prisoners? Who designs research? Do other people view us through their own lens of power, privilege, moral values, frameworks, perspectives?’

She likened the feeling of being ‘participant A’ in research to that of a ‘lab rat’ being investigated for their vulnerabilities and trauma. Paula argued that to build trust in research, three things need to change. One, we must have knowledge equity; two, we need to research issues that matter to people who have been directly impacted; and three, we must emphasise researching their strengths and the conditions needed to drive systemic change. The research must also be used to drive change and improve outcomes, not merely as an academic piece (such as a PhD).

Policing

Dr Ben Bradford described one definition of trusted research that is being widely adopted: ‘to make yourself willingly vulnerable to that institution under conditions of trust.’ He explained that we call the police because we have positive expectations and evaluations of what they will do to help/support. We believe that they will be well intentioned and competent. However certain groups in society have different expectations and evaluations due to their experiences and therefore they will perceive it to be riskier to make themselves vulnerable. If you have low levels of trust, you are less likely to call the police.

He argued that we need to see trust as a process, a continuum, a spectrum. He also identified the difference between trusting individuals and trusting institutions and the interplay between them, as well as the role of vicarious trust, i.e. through hearing the experiences of friends and family or through the media. This means that you might trust a particular neighbourhood officer, but not trust the police as an institution:

‘That is why recent scandals from the top and centre are so destructive. We need to trust the institution of the police. The solution to build trust is often seen as being down to individuals and neighbourhood policing, but we need to think about building trust in the centre.’

Prisons

Hindpal Singh shared the results of HM Inspectorate of Prisons research into the experience of Black people in prison. The research found that Black people have far lower levels of trust in the system than white people. He queried ‘Is it ever possible to have trust in a prison environment?’. He further explained the added complexities involved in measuring and building trust in custody, given officers must be alert to, identify and calibrate risks, but also must show trust in order to support rehabilitation. Staff have various tools to help them measure risk and trust – from assessment tools like Oasys, to personal intuition and instinct. The research shows that a more creative and different approach is needed going forward to build trust between staff and Black people in prison.

Young adults and language

Nadine Smith and Karene Taylor from Leaders Unlocked called for the CJS to take a holistic perspective of young adults and to treat them as a distinct group. They shared personal childhood experiences of witnessing police raids on their homes and detailed the impact of their trauma, which in turn led to mistrust, especially as this trauma wasn’t acknowledged or addressed.

They also highlighted that racial disparities in sentencing (‘same crime, different time’), which they experienced and witnessed, destroys trust.

They called for children and young adults who witness violence at home or are neglected or exploited, to been first seen as victims. They also described the importance of language and treating people as humans:

‘I’m hearing the term prisoner – what about person in prison? I’m hearing offender – you mean person, human being. Once we start humanising and seeing people as individuals, theywill be more receptive. Treating and talking about people as humans, whether it is researchers, or staff in prisons or probation, would help build trust.’

Lastly, they called for recommendations about how to fix the broken criminal justice system to be implemented, as lack of action and accountability breaks down trust:

‘Imagine the CJS is a car. Would you keep driving a car that keeps breaking down all the time? If the system is broken and there are recommendations to make it better, then fix it. There are so many reports, but how many recommendations are actually done?’

Afternoon workshops

During the afternoon participants chose preferences for two interactive 50-minute workshops from the following themes related to trust:

- Public trust

- Trusted relationships and practices

- Trusted spaces

- Risk versus trust

- Trusted research

- Inequality and mistrust

- The reach of the criminal justice system

Formal presentations were banned to maximise participation and dialogue.

Crisis and scandal

Dr. Harry Annison (Southampton Law School)

Dr. Annison presented his ESRC-funded impact project ‘Exploring the role of crisis and scandal in contemporary penal policy: challenges and opportunities’, a collaborative project with the Prison Reform Trust’s Building Futures programme which considered issues that are central to the dynamics of penal change in two ways:

- Scholarly work on theoretical perspectives on the concepts ‘crisis’ and ‘scandal’

- Knowledge exchange activities with a range of key criminal justice stakeholders

The issue of trust – conceptualised primarily as perceived legitimacy by various audiences in the criminal justice system –was integral to this work which reflected upon how crises may hinder trust by groups in the criminal justice system, the role of leaders, and how trust might be built in a less punitive CJS.

Dr. Annison introduced participants to the research, before posing questions to the participants. The central question was ‘How can progressive penal policy, and practice, be achieved in a context where the reality and anticipated threat of crisis and scandal are ever-present?’

Participants also discussed:

- How moments of crisis and scandal had influenced their own work, what challenges and opportunities they presented and how they navigated them.

- How consistent progress towards positive change could be protected from derailment

- Whether specific crises or scandals can be used to enable or propel positive change?

- How change can be achieved in a context in which public expectations for transparent, democratic and inclusive governance – and the ‘pressing in’ by the public on policy issues via social media – are ever-increasing.

Additional resources

- Annison (2020) ‘Re-examining risk and blame in penal controversies. In, Pratt, John and Anderson, Jordan (eds.) Criminal Justice, Risk and the Revolt against Uncertainty. Palgrave

- Annison (2022) ‘The Role of Storylines in Penal Policy Change’ Punishment & Society 24(3) 387-409

- Annison and Guiney (2022) ‘Populism, Conservatism and the Politics of Parole in England and Wales’ Political Quarterly 93(3) 416-423

- Guiney, T. C. (2022). Parole, parole boards and the institutional dilemmas of contemporary prison release. Punishment & Society Online First

- Annison, H., Guiney T and Rubenstein, Z. (2023) Locked in: a discussion paper, Prison Reform Trust

Building trust amongst the public using framing

Sophie Gordon, FrameWorks UK

FrameWorks is a think tank which aims to build understanding about systems and issues in order to lead to positive change. Building understanding and building trust go hand in hand. The better that people understand an issue, and the solutions to problems, the more likely they are to support those solutions. The session approached the theme of trust from the angle of FrameWorks’ work focused on building trust in progressive solutions.

Sophie Gordon commenced the workshop by sharing insights from FrameWorks’ research into how people understand criminal justice in the UK, and how we can reframe the conversation. The floor was then opened up for reflection and discussion with people in the room.

Participants looked at the obstacles that needed to be overcome when communicating about criminal justice. These included:

- Blame and individualism

- A tendency to dehumanise people with convictions

- A lack of understanding of what rehabilitation looks like and how it works

- Fatalism – the sense that the problems we face are so big that “I don’t think anything’s ever going to change”

Participants then focused on a particular aspect of Frameworks research: metaphors which can be used to open up understanding about how things work and what solutions might be needed. Metaphors are helpful as they provide a simple and concrete comparison which builds understanding in a very immediate way. Crucially, metaphors need to be tested to ensure they are building the desired understanding.

Two examples were shared:

- ‘Channelling crime’, which builds understanding of why alternatives to prison are needed:

‘Sending people to prison for minor crimes is like pushing them into a powerful current that sweeps them further into crime channels.’

- ‘Bridges from prison’, which helps people to understand the role that training and employment, and family connections, play, and why they are so needed:

‘Leaving prison is like crossing over a wide river, and people leaving prison need bridges – like stable jobs and family connections – to make their way to stable ground.’

Additional resources

See FrameWorks research briefings and toolkits, here: https://frameworksuk.org/resources/tag/justice/

Trust in young adults (and vice versa)

Nadine Smith and Karene Taylor, Leaders Unlocked

The purpose of this workshop was to explore how adults working in the criminal justice system gain trust from the young people they work with as well as to consider the opposite i.e. how adults build their trust in young people. This is important on both sides because many young people in the criminal justice system do not trust the adults they work with, and this leads to a disconnection. For example, if a young person doesn’t trust the adult they are working with they may not be able to communicate the help they need in certain areas, or be able to express their worries and wants. On other side, some adults have a certain mistrust of the young people they work with in terms of what they say or what they do which in some instances leads to the help a young person needs not being given. Asking both questions was seen as important because where such questions are asked, practitioners and academics often only ask the first half of the question and not the second.

In the workshop, the presenters engaged participants in a visual activity: playing Jenga which was renamed ‘the Tower of Trust’ where anyone could step up pull out a piece and say what that piece represented in the breakdown of trust in adults. As the game went on, and the tower broke down, participants were then asked to build it back up with the pieces representing what builds trust in adults.

Key themes

In relation to the first part of the activity, some of the themes around what destroyed young people’s trust in adults were:

- Negative interactions and reinforcement of labels

- Lack of support for parents/carers from professionals who could help e.g., youth workers, people in education, criminal justice system agencies

- Exploitation

- Lack of representation for themselves and their experiences

During the second part of the activity focusing on what it takes to build trust in adults the following themes were raised:

- Trust is rebuilt over time i.e. can take some time for adults to build or rebuild trust in young people {and vice versa}

- How showcasing lived experiences can improve transparency i.e,. demonstrating involvement with young adults so they can see it first hand

- The importance of accountability and legitimacy of professionals

- The need for redistribution of funding, including for training and support

- The importance of autonomy

- Understanding that young adults are developing, meaning they should be considered as a separate cohort with particular needs.

Additional resources

Shame, violence and trust

Prof. Roman Gerodimos, Bournemouth University; Jonathan Asser (Shame/Violence Intervention) and Charlie Rigby (The Violence Intervention Project); Sandra Barefoot, The Forgiveness Project

In this experiential workshop, participants explored the relationship between shame and trust, drawing on a recently published book Interdisciplinary Applications of Shame/Violence Theory: Breaking the Cycle (Palgrave Macmillan 2022, ed. by R. Gerodimos) and the work of prominent American psychiatrist James Gilligan, which considers shame as a key driver of violence.

At the start of the session, participants were invited to take some time to reflect and use crayons and paper to draw the concepts of shame and trust. This simple exercise produced a fascinating range of drawings rich in colour, symbolism and depth, and helped us begin to unpack and understand the intrinsic relationship between the two concepts.

Participants discussed the following themes:

- Shame often stems from a breach of trust; and this works across all levels of analysis, from the interpersonal and domestic to the political, systemic and international level. For example, victims and family members who feel that the criminal justice system has failed them – by not treating them with dignity or by not producing a justice outcome – are less likely to trust it.

- Suspects and perpetrators of crime who have been shamed by the system, by journalists and/or by the public at large are less likely to trust the system.

- Equally, trust-building measures are an important first step to managing and overcoming shame.

- For people with lived experience of prisons, it was the lack of choice that triggered shame.

In parallel to the substantive discussion on the meaning, role and interaction of shame and trust, facilitators modelled the shame/violence dynamics of the group in real time, by critically reflecting on the potential interpretations and emotional consequences of interventions made by facilitators and participants on others in the room. This provided an experiential understanding of the shame/violence model.

Additional resources:

- Episode 69 of The Reset by Sam Delaney, featuring Jonathan and the book https://www.listennotes.com/podcasts/the-reset-by-sam/ep-69-jonathan-asser-8SIoH5y4s1d/

- Shame/Violence Intervention (SVI) – Jonathan Asser: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F-3xqz2lt5c on YouTube

- The Forgiveness Project: https://www.theforgivenessproject.com/, which also features a podcast

- VIP: The Violence Intervention Project - https://vip.org.uk/

- Gerodimos, E 2022, Interdiciplinary Applications of Shame/Violence Theory: Breaking the Cycle, Springer Nature, Cham, Switzerland, Chapters 1 and 2.

- Gilligan, J., 2003. Shame, guilt, and violence. Social Research: An International Quarterly, 70(4), pp.1149-1180.

Trusted prison relationships

Prof. Rosie Meek, Prof. Nick Hardwick and Kim Reising, Royal Holloway University; Dr. Sarah Waite, Leeds Trinity University

Professor Rosie Meek, Professor Nick Hardwick, and Dr Kim Reising, a team of researchers from Royal Holloway University of London, presented their ESRC funded research project “Secondary analysis of data collected over a 20-year period by HM Inspectorate of Prisons”. They collaborated with Dr Sarah Waite from Leeds Trinity University who presented her findings from grounded theory-led research on the complex and power-intertwined nature of trust within carceral institutions.

In the first part of the workshop, participants grappled with quotes and themes from Sarah Waite’s research on trust in a women’s open prison. She presented the following taxonomy of trust and explained that she had identified three levels of trust within the institution.

Dr Waite explained that trust in prison environments is complex and need they fail to address power imbalances in prison where the line between interpersonal and institutional trust gets blurred since prison workers build relationships with prisoners but also represent prison infrastructure.

- Forced trust refers to a person having to trust someone, even if they do not want to.

- Carceral trust refers to trust based on a compliant relationship with competent staff, e.g. when staff were able to generate a level of trust through the successful work they did with prisoners.

- Thick trust refers to strong interpersonal trust being built as a result of certain roles fading into the background. e.g. concepts like prisoner, prison guard, and even prison itself were disregarded, paving the way to a person-centred relationship.

Participants discussed several themes:

- The question of how an interactive, trusting, relationship can be built when a power imbalance exists that allows the prison to dictate who is trustworthy?

- The ethics of even talking about trust in the relationships between those on either side of the prison bars was questioned, particularly in light of the way the prison system distorts the meaning of trust e.g. participants in the research were in open prisons because they were ‘trusted’ by the criminal justice system; trust in these women was taken away when they were imprisoned and returned only in a mutated form that still controlled them, albeit in open conditions.

- A line was drawn between trust, which is an interactive connection, and trustworthiness, an individual trait imparted onto the women.

- The challenges practitioners face in their attempts to build trusting relationships with prisoners within a strict prison framework. This constrains the relationships they are allowed to build, limiting their ability to foster trust. Perhaps the only way for prison officers to garner trust is by detaching themselves from the prison system (e.g. by disregarding prisoner/prison officer roles).

The Royal Holloway team provided a unique insight into one of the largest databases of prisoners’ self-reported lived experiences. Using worked examples, they demonstrated how this ground-breaking resource can benefit trust research and enhance understanding of staff-prisoner relationships.

Participants discussed the impact of making this database accessible to the wider research community, as it has the potential to not only promote and improve trust in criminological research, but also in the overall criminal justice system. The discussion was centred around key questions such as how trust in the criminal justice system can be defined and measured and what factors, such as providing access to data on lived experiences of those impacted by the system, can inform and improve decision- and policy-making processes in order to promote trust in the criminal justice system.

The showcasing of quite different approaches to prison research and involvement of participants from diverse disciplines contributed to a holistic understanding of trust in the criminal justice system. The participation of individuals with professional experience in prisons and the criminal justice system in the discussion was particularly valuable, as it provided further real-world insights and perspectives that enriched the conversation. The workshop facilitated meaningful dialogue on how trust can be promoted in the criminal justice system and allowed the researchers to receive initial feedback from potential data users.

Additional resources

Dr Sarah Waite’s work was heavily influenced by the research of Hannah-Mofat, e.g. Hannah-Mofat, K. (2000) ‘Prisons that Empower’, British Journal of Criminology, 40(3), pp.510 –531.

The Inspection survey data can be explored via the UK Data Service. More information about the Royal Holloway research project can be found here and the handout of the workshop session is freely available here.

Empathy and trust

Carlotta Gouldon, Central St. Martins, and Alexa Wright, University of Westminster

Carlotta Goulden and Alexa Wright collaborated to facilitate a workshop focused on how storytelling methods could be used for building empathy and trust in various ways – building trust with the CJS as an establishment, to gain a level of trust with participants that allows them to be vulnerable and attempting to build trust between people impacted by the CJS and the public.

The workshop facilitators discussed how they went about building trust in their research which centres on an artistic approach supporting people in prison to express their stories and experience using visual or digital media.

Themes discussed included:

- How being an artist and educator can help to navigate the HMPPS National Research Committee, the first step towards being trusted as a researcher.

- Exchanging stories, including those generated through lived experience, can help build trust with people in prison and help to generate empathy. All researchers can work to create empathetic environments when working with people in the CJS.

- The use of objects as a means of building trust through authenticity. E.g. asking participants to bring objects that were important to them can humanise all those involved, putting the person-to-person interaction first. A further benefit to this was that they found people would talk more when they were handling objects.

The session proceeded with a discussion of what digital storytelling can achieve and what success might look like. For the facilitators, such storytelling was seen as an inherently activist approach, helping people to understand and tell their story through co-production and using that story to raise awareness and (hopefully) effect change. Stories often include aspirations which support change within individuals and creating multiple stories at different times can concretely show change.

Finally, a few points were made about measuring success. First and foremost is that the people involved gain something from it, whether that be the technical skills to create these expressions (e.g. video editing), emotional growth, or a progression in their life. Beyond this, creative projects like these should look to disseminate the messages included in the media they create. By making sure these are listened to, researchers may begin to interrogate the conception of ‘normal’ and challenge it so as not to marginalise people in the criminal justice system. In this way empathy with people in the CJS might be built, resulting in greater trust among society and leading to improved outcomes for all.

Additional resources

Examples of this kind of work can be seen in Alexa Wright’s book A View from Inside, or on Stretch’s page here: https://vimeo.com/stretchcharity.

Creating a trustworthy learning space in prison

Dr. Ross Little (De Montfort University) and Dr. Morwenna Bennallick (University of Westminster)

Dr Ross Little and Dr Morwenna Bennallick collaborated to consider how to create trustworthy learning spaces.

The purpose of the session was to explore, with the group, what it means to experience a trustworthy learning space. Workshop leaders wished to illustrate their experiences of trust and trustworthiness in classroom spaces in prisons, drawing on their experiences of developing prison-university partnerships and to reflect with participants on what this might mean going beyond the prison classroom to university learning spaces and how these spaces might be made more accessible. These themes were important to consider in the context of trust because a sense of trustworthiness can be difficult to establish in low-trust contexts such as prisons, where the institution holds people in a state of prolonged wariness, or diffidence. Moreover, a focus on trustworthiness helps transfer the emphasis away from individual learners and onto the facilitator and the space. Rendering a space trustworthy, especially in a low-trust context such as prison, is valuable. There are likely to be important lessons that transfer to other learning contexts, such as universities (which some people may also experience as uncomfortable or low trust contexts).

The workshop leaders began the session by inviting participants to tell them about a time they experienced a trustworthy learning space. They tended to highlight examples of relatively informal learning experiences, where they felt sufficiently comfortable and not judged. A couple of responses referred to a particular individual who had made them feel like they belonged in the space. A teacher, as a leader in the space, can play an important role in setting the tone. Ross and Morwenna then presented their findings from their research and development work with prison-university partnerships.

Key themes from discussion

- Abstract questions help us level the playing field, handing over some of the discursive power in the classroom space

- Discussing difficult or uncomfortable subjects is best done when a degree of comfort and trust has been established in the space

- Trust can be fragile and it may not always be appropriate to trust too quickly/easily

- Universities might become trusted spaces for people in prison and leaving prison

Additional resources

- Bennallick, M. (2019). The Open Academy: An Exploration of a Prison-Based Learning Culture (Doctoral dissertation, Royal Holloway, University of London).

- Little, R. & Warr, J. (2022). Abstraction, belonging and comfort in the prison classroom. Incarceration, 3(3).

- Little, R. (2023) The Prison Mug: Perceptions of Permission, blog for Sensory Criminology.

Reset, restorative spaces in prisons

Charlotte Calkin (Restorative Engagement Forum), Dr. Lucy Willmott (University of Cambridge), Jane Dring (online), and Jacob Dunne

This session was run as a run as a restorative conversation. Participants were introduced to research on a restorative justice project run in three prisons. The ReSeT model is a course designed to embed restorative approaches within prisons by supporting men to develop their communication skills to improve their relationships with other residents, officers, other professionals they are working with and with their families and loved ones.

The facilitators explained that this is not restorative justice in the traditional sense but a suite of skills to build relationships and better environments thus developing trusting safer communities. They then presented their findings on what aspects of the project have worked, the tangible benefits and the obstacles and discussed with participants how embedding communication skills builds more trusting environments and what that looks like in practice.

Jacob Dunne gave an overview of restorative skills and how they benefit building trusting environments. Dr Lucy Willmott shared her research on ReSeT, including the most recent iteration of the model in which the men deliver the work themselves. Jane Dring shared her experience of implementing the course, primarily in HMP Warren Hill with feedback from Warren Hill. Charlotte Calkin introduced the principles of restorative approaches and how they build trusting communities.

Participants discussed the following areas:

- Creating a trusting environment by the use of circles.

- How the course is delivered and how that builds trust in communities i.e. which model gets best benefits for learning, safety, trust etc. e.g. The men’s feedback that they would not be so open if the course was delivered by programmes or psychology.

- Accreditation vs. voluntary participation and how accreditation might undermine trust by removing the voluntary element.

- The benefits of reflective and safe communication to build trusting environments and how this impacted on the relationships between men, relationships with the prison.

- The role of vulnerability

- Building confidence (trust) in the benefits of the course

Additional resources

Calkin, C. and Willmott, L. (2022) Relationship skills based on restorative practice principles, Clinks blog

Willmott, L. (2022) A process evaluation of the restorative practice Relationship Skills Training (ReSeT) Model

Trust in prosecution decisions

Neena Samota, St. Marys University; Sharon Grant and Varinder Hayre, Crown Prosecution Service; Deputy Chief Inspector Yasmin Lalani and Chief Inspector Peter Bodley (Metropolitan Police Service)

The aim of this session was to illustrate the problem of trust and confidence in the criminal justice system through the discussion of fictitious examples of work between the police and the Crown Prosecution Service, how they work together to build a case and how prosecution decisions could be scrutinised. Facilitators presented a series of three ‘incidents’ of suspected hate crime— defined by the Law Commission as hostility or violence directed at people because of who they are—which the police had come to the CPS with to ask for decisions because they are unable to charge by themselves:

- In January 2022, a defendant travelled from Wales and assaulted 3 male victims in Southall who were all wearing the Sikh attire (Long white shirts and Turbans) and they had long beards. Victim 1 was facing an Indian Restaurant when he was hit by the defendants with an umbrella on the side of his arm. The defendant walked away. The incident was captured on CCTV.

- The second victim was 17 and going to his Punjabi school when the defendant approached him and hit him with a bag on the side of his arm. The victim recognised him from the newspaper and the incident was captured by CCTV.

- The third victim was going to the Gurudwara (the Sikh temple) when he was punched, fell on the metal railing, lost consciousness, and broke his leg. This was captured on CCTV. The defendant’s brother recognised him from the police appeal leaflets and reported the incident to the police. The police arrested the defendant. A doctor examined the defendant at the station and concluded that he had no mental capacity and was not fit for the interview.

Participants were asked whether they would prosecute in each case. They were asked to consider a range of perspectives:

- Scrutinise: scrutinise a fictious case.

- Engage: with specific points in the process where either the police or CPS could have done more/better in identifying risks involved.

- Assess: Assess at which point issues of trust and confidence intersect with decision making to consider where trust is located.

- Identify

Themes discussed included:

- How can we develop better trust and relationships with trust, including within the wider community, and what builds public trust in decisions made by police and CPS in their work

- The value of scrutiny panels and police training in supporting dialogue with the community and gaining trust from the community.

- At which points criminological inquiry can be helpful

- The pathway of mental health help and rehabilitation as an alternative to prosecution.

Additional resources

Kirat Kaur Kalyan & Peter Keeling (2019) Stop & Scrutinise: How to improve community scrutiny of stop and search, Criminal Justice Alliance

Home Office (2023) Draft Community Scrutiny Framework: National Guidance for Community Scrutiny Panels.

Technology and Trust: co-producing digital media to promote desistance

Jason Morris (Senior Policy Manager, His Majesty’s Prison & Probation Service; HMPPS) in collaboration with Darren Tipton (Peer Mentor, East Midlands Probation) and Jack Bennett (Peer Mentor Coordinator, East Midlands Probation).

The views expressed in this summary are those of the author and are not intended to set out HMPPS policy on co-production.

Co-Producing Digital Media to Promote Effective Probation Practice

Co-production can create a context in which ‘offenders’ are given a role as ‘experts-by-experience’ (or ‘co-creators’) whose insights can be unlocked to improve services. This workshop focused on the ideas of risk and trust during the co-production of a short video called ‘Probation Myths and Realities’. The video was made to support constructive conversations between HMPPS staff and people resettling into the community to help build trust and support desistance.

Making the ‘Probation Myths and Realities Video”

This project was conceived and coordinated by Wayne Lambert (East Midlands Engaging People on Probation Lead). Wayne’s team of Peer Mentor Coordinators recruited three co-creators (including Darren). Darren and Jason explained to participants the valuable work done by the team in helping co-creators to prepare, coordinating their travel, and creating a safe space to work together. During the project, having gained informed consent from co-creators, Jason recorded an unscripted conversation between them about their insights into the ‘myths and realities of probation’. He later edited the audio recording and combined it with visual stock footage to make a two-and-a-half-minute video. Finally, the video was created with feedback from co-creators who gave informed consent to use the material. During the workshop, Darren explained his perspective of the co-production process, his thoughts about the video, and what he took away from the experience.

Reviewing the Outputs of Co-production

Having shared the video with participants, Jack summarised the feedback from a user-testing process which was captured by Peer Mentor Coordinators as people waited for probation appointments. Jack spoke of the value of giving information using voices and stories of lived experience. Participants saw how the video would help answer questions they had about probation, particularly at the start of their time on probation. They also identified areas for improvement. For example, some respondents said the video’s use of stock footage did not feel authentic and the messaging might feel unrealistically positive for some people.

Reflections from the Workshop

Participants in the workshop appeared to share a belief in the potential of co-production to build trust in probation settings. The limitations of the approach were also discussed, given the power imbalance between ‘co-creators’ and ‘the authority’. In line with the CJA Symposium’s theme, participants also reflected on the risks people faced when sharing their lived experiences with wider audiences and the implications of their stories being used to influence others. The workshop concluded with a discussion about risk and trust in the development and use of other technologies with the potential to support desistance (e.g., Learning Platforms, Virtual Reality, etc).

Additional resources

You can read more about approaches to co-producing digital media in justice settings here:

Prison Service Journal (crimeandjustice.org.uk)

Trust in sentencing decisions: guilty pleas

Dr. Jay Gormley, University of Glasgow

Dr Jay Gormley supported participants to consider the question Should plea bargaining be abolished to improve trust in the justice system? Dr Gormley introduced participants to the practice of ‘sentencing discounting’ (or the sentence differential) – applying a reduced sentence where the accused pleads guilty drawing on his research, including work conducted for the Scottish Sentencing Council in 2020.

Participants were asked to respond to a series of questions:

- What principles do you think the justice system should adhere to when convicting and sentencing people who have committed crime?

- What do you understand of plea-bargaining practice?

- Does plea bargaining pose any challenges for the points you identified above?

- Whose trust (if anyone’s) might be positively or adversely impacted and in what way?

- Could a change of presentation/terminology help build public trust? Discount vs reduction. Negotiation vs bargaining?

- Should plea bargaining be abolished, left unchanged, or altered?

Participants discussed a number of themes

- The relationship between sentences imposed and the sentences served and the extent to which that is ‘truthful’ or transparent

- The potential for coercion and ulterior motives within plea bargaining processes e.g. to secure a conviction/outcome or cost cutting

- The capacity of young people to make informed decisions about pleas

- How plea bargaining relates to the principle of ‘innocent until proven guilty’ and ethics of someone plea bargaining if they are innocent

- The impact of plea bargaining on risk assessments

- Implications for justice, equality and trust for victims and if people get different sentences for the same crime

- The potential for reforming plea bargaining and changing its name e,g. in some countries it is related to as a sentence discount

Additional resources

Dr Jay Gormley, Dr Rachel McPherson and Professor Cyrus Tata, ‘Sentence discounting: sentencing and plea decision-making’ Scottish Sentencing Council, December 2020

Knowledge equity in criminological research

Dr. Donna Arrondelle (University of Southampton) and Marc Conway (Prison Reform Trust)

“Knowledge equity is the commitment to focus on knowledge and communities that have been left out by structures of power and privilege, and to break down the social, political, and technical barriers preventing people from accessing and contributing to free knowledge” (Campbell, 2022).

The aim of this workshop was to think through the research process in terms of building trust in concrete ways between experts by experience and academic researchers. The facilitators discussed their experiences of research collaborations and reflected with participants on ways to develop trust using their recent collaboration, a co-produced academic paper on friendships during incarceration, as a springboard for discussion.

The group, consisting of academics, experts by experience, freelance creatives working with the criminal justice system (CJS), and students, had a lively discussion covering much ground. Three key inter-related issues stood out.

The unintended negative impact of institutional ethical regulations

Anonymity is not inherently good in research. In fact, for some individuals invited to share their experiences it can elicit a dehumanising effect. Becoming ‘Participant A’ and being stripping of names can have an invisibilising impact, potentially compounding stigma. There is an inevitable tension here between researcher aims of protecting identity to avoid discrimination and stigma and individual participant’s desire to be seen and heard. Formal ethics procedures require anonymity for any ‘vulnerable population’ prohibiting visibility, which in turn can erode trust.

The absence of continued consent

The process of consent was also criticised by some in the room, feeling that there needed to be opportunities to withdraw years down the line. That consent is given in a particular space and time was highlighted. For example, research involvement could be strategic as advantageous for parole hearings and others made the point that involvement was not about the research per se but about adding variety to the mundane daily prison routine. It was suggested that trust would be cultivated if there were opportunities to withdraw later, potentially years later, especially important if names were attributed.

Power imbalances between researcher and researched

Although co-production and knowledge equity approaches seek to enhance trust through further disrupting power imbalances between experts by experience and the researchers/ institutions they choose to work with it was acknowledged that equality within current academic structures is impossible.

Participants agreed that there are not simple solutions to these structural challenges and barriers to trust. However, there was near consensus in the room that academic institutional norms need to shift to increase capacity for trust with knowledge equity being fundamental. It was suggested that academics sitting on ethics committees need to be alerted to these barriers to trust and institutions will need to meaningfully confront these tensions if the academy is serious about increasing meaningful co-production with individuals outside of academia, justice-involved or otherwise.

Black communities’ trust in the police

Abigail Shaw and Jen Harris (Birmingham City University)

Abigail Shaw and Jen Harris are PhD students from Birmingham City who collaborated to consider their emerging research on black communities’ trust in the police and share their varied experience of navigating the criminal justice sector. The purpose of the session was to initiate conversations and raise awareness around the overarching theme.

Following a brief introduction and an insight into several elements, to support participants’ understanding of the (somewhat tenuous) relationship between Black Communities and Policing, participants were divided into three groups and allocated a specific topic and case example(s).

The groups were asked to collectively develop responses and considerations to the below questions:

- What are the common factors pertaining to this theme that influence distrust in the Police?

- What needs to be done to improve trust?

- Is knowledge around policy and legislation vital to enable change? If so, where’s best to start?

Key themes of discussion included:

- The adultification of young people

- The impact on trust of repeated failure from the police

- The importance of speaking out about negative experiences of the criminal justice system and the need to recognise the impact on mental health, which required more resources.

- Scope for more education e.g. one participant was from a theatre company that uses theatre to address criminal justice issues, she goes into schools to teach about the criminal justice system.

- Greater consideration of systemic issues, particularly within the police, including culture and power dynamics contributes to the problem.

- The need to create different spaces, away from the police, for people who have mental health issues.

Additional resources

Jacobs, M.S. (2017), The Violent State: Black Women’s Invisible Struggle Against Police Violence, 24 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 39

National Police Chief’s Council and College of Policing (2022), Police Race Action Plan: Improving Policing for Black People, College of Policing

https://migrantwomenpress.com/the-overlooked-reality-police-violence-against-black-women-in-the-uk/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-35481787

Mayor of Police of London Office for Police and Crime (2019), Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG), MOPAC Evidence and Insight

Davis, J. (2022), Adultification bias within child protection and safeguarding, HM Inspectorate of Probation.

30 Sept 2021, ‘Ahead of Black History Month, Refuge call for better protection for Black women experiencing domestic abuse’.

See also Sistah Space: a grassroots organisation that provides shelter and community for women and girls of African heritage.

Scrutiny and trust

Dr. Hindpal Singh Bhui, HM Inspectorate of Prisons/University of Oxford and Alexa Reed, College of Policing

Dr Singh Bhui and Alexa Reed collaborated to consider personal trust and trust in criminal justice institutions like the police and prisons. Hindpal presented his thematic research in seven prisons on the experience of black prisoners and black staff which strongly demonstrated the lack of trust between black prisoners and white staff. The Inspectorate also found relatively weaker relationships between prisoners and staff were affecting many other outcomes, e.g. quicker resort to use of force and escalation of violence. Black staff felt they were not trusted to do their jobs and lacked avenues to promotion. Alexa Reed introduced participants to workstreams to build trust that the College of Policing had established in the aftermath of the death of George Floyd and growth of Black Lives Matters movements, including scrutiny groups, improved communication and options for reconciliation.

Workshop participants discussed what would help facilitate building relationships between police and prisons and those involved with them. Themes included:

- How trust is likely to be impacted by change and the importance of taking responsibility by understanding patterns and trends and taking feedback from the public.

- Considering options for reconciliation with communities including, listening to them, repairing previous harm and changing practice to address existing harms and restorative justice.

- The importance of accountability and (in)effectiveness of existing scrutiny mechanisms like independent custody visiting schemes.

- The potential for small changes to have a cumulative effect on building trust.

- Importance of focusing on the motivation of professionals to change as part of change initiatives.

Additional resources

Jonathan Jackson, Tom R. Tyler, Ben Bradford, Dominic Taylor and Mike Shiner (2010) Legitimacy and procedural justice in prisons, LSE research online

HM Inspectorate of Prisons (2022) The experiences of adult black male prisoners and black prison staff.

HM Inspectorate of Probation (2023) Inspectorate research demonstrates clear link between high-quality supervision and reduced reoffending for people on probation

LGBTQ+ hate crime reporting

Professor Pippa Catterall, University of Westminster

Professor Pippa Catterall facilitated a workshop to discuss the relationship between trust and the steady increase in the number of recorded hate crimes committed against members of LGBTQ+ communities. Surveys by Galop suggest that some 80% of these crimes go unreported because LGBTQ+ people either do not trust the police, and/or are apprehensive about how they will be treated by them. Yet only limited research has been conducted into these types of hate crimes. Indeed, much of the existing research into hate crime is generic and does not address the specificities of the experiences of marginalised groups like LGBTQ+ people. Furthermore, the studies that have been conducted on LGBTQ+ targets of hate crime largely concentrate on the impact on the victim, rather than the motives of the perpetrators.

Workshop participants discussed:

- The need for the police to understand the nuances of LGBTQ life experiences and related adversity.

- The scope for greater insight into why and where these crimes take place and how people involved are experiencing the criminal justice system. For example, hate crimes happen less in ‘gaybourhoods’ but will happen upon leaving.

- Lesbians who do not respond to male sexual advances or ‘banter’ may find themselves targets.

- The importance of the word queer and the need to reclaim it.

Additional resources

This research forms part of a wider project on Queering Public Space. See for example, 2021 report. Research into the desistance of hate crime, and its intersection with the built environment, is a key part of this work.

Ellis, S.J., Riggs, D.W., and Peel, E. (2019) Prejudice, Discrimination, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Intersex, and Queer Psychology: An Introduction, pp. 187-209.

Roberts, C., Innes, M., Williams, M., Tredidga, J. and Gadd, D. (2013) Understanding who commits hate crime and why they do it, Welsh Government Social Research.

Valentine, G. (1993) (Hetero)Sexing Space: Lesbian Perceptions and Experiences of Everyday Spaces in Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, Volume 11, Issue 4.

And see related work e.g. Goh, K. (2019) Sex work is urban, International Journal of Urban and Regional.

Joint enterprise

Nisha Waller, Oxford University

Nisha Waller facilitated a workshop on ‘joint enterprise’, criticised for bringing disproportionate numbers of young black and black mixed-race men on the periphery of a criminal offence into the scope of criminal prosecution. Trust was considered in the context of the unequal application of joint enterprise, largely attributed to erroneous application of the stereotypical ‘gang’ label which serves to construct a ‘common intention’ between defendants.

Nisha presented the findings from in-depth interviews with young black and mixed-race men who had been indicted or convicted of murder as a secondary party, as well as legal practitioners with experience prosecuting or defending in joint enterprise murder trials. Most of the young black and mixed-race men who took part in the study made it clear that they did not trust the police. For most, this was a result of constant police harassment and experiences of police brutality. For some, their experience of joint enterprise exacerbated this distrust, as their conviction brought the legitimacy of the whole criminal justice system into question. The research highlights how ‘trust’ is a two-way process. The longstanding distrust of black communities has a role to play in the racialised application of joint enterprise, as young black men continue to be perceived through a lens of ‘risk’, assumed complicit in an offence, despite their lack of physical contribution to the crime.

Themes discussed included:

- Often discussion about trust and the criminal justice system asks ‘why don’t the black community trust the criminal justice system?’ when there is equally a question about ‘why the police and prosecutors don’t trust young black men’

- Narratives around gangs and previous arrests are prosecution arguments commonly used in court

- The limited application of joint enterprise i.e. it happens in white collar corporations but when prosecuted is not centred around the narrative of gangs.

- Wider challenges in how these narratives and racial prejudices play out within juries i.e. how do you convince a jury that someone did something when they didn’t, especially with something as subject as foresight

Additional resources

Book: Gang Narrative and Broken Law – Nisha Waller https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/resources/gang-narratives-and-broken-law-why-joint-enterprise-still-needs-fixing

Jailed over a group chat, Channel 4 Documentary, Hallmarks of Joint Enterprise

Clarke, B. and Williams, P. (2020) “(Re)producing Guilt in Suspect Communities: The Centrality of Racialisation in Joint Enterprise Prosecutions”, International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 9(3), pp. 116-129. doi: 10.5204/ijcjsd.v9i3.1268.

Criminalising poverty

Dr. Rona Epstein, University of Coventry

Dr Rona Epstein facilitated a workshop on how we can trust a justice system that punishes poverty, disadvantage and mental illness. Dr Epstein began by presenting her research illustrating how people are committed to prison who have not been charged with a crime and who have evidenced mental ill-health by examining the rarely discussed issues concerning imprisonment for contempt of court when people break civil injunctions.

She described how, what she terms as ‘invisible people’—the most vulnerable members of our society in terms of their poverty—are effectively criminalised in civil courts and questioned the current punitive approach to anti-social behaviour when they could be dealt with by social welfare provisions related to mental health rather than the court. Civil injunctions lack important legal safeguards i.e. there is no right to a lawyer or other representation, no legal aid, no obligation for the order to be explained to the person being charged and no requirement for a pre-sentence report.

Participants in the workshop discussed several case studies to illustrate the ways in which civil injunctions have been used and their impact. Themes discussed included:

- The need for proper public data to address the lack of transparency/data over how many people are in jail under civil injunctions.

- The importance of training civil court judges about criminal law.

- The extent to which judges have discretion in such cases.

Additional resources

https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/resources/now-more-ever-penalisation-poverty-must-stop

https://revolving-doors.org.uk/action-areas/rethink-reset/

https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/resources/go-directly-jail-shouting-begging-and-rough-sleeping

System mapping workshops

System mapping is a way of visualising a system and to explore the connections and relationships between different parts of it. The process of system-mapping aims to encourage discussion, debate and shared understanding from different perspectives.

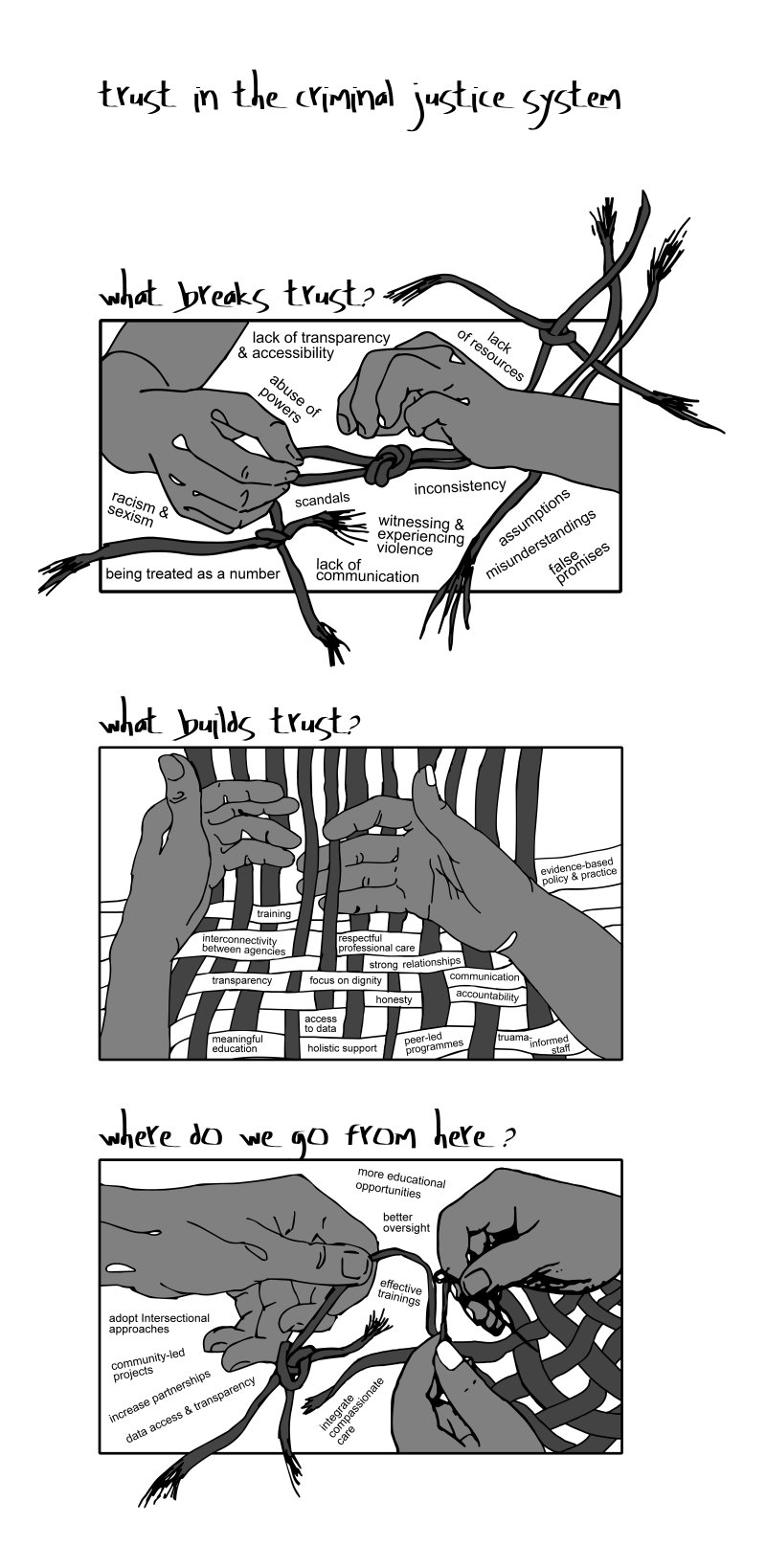

Nina Champion and Gemma Buckland facilitated a series of three workshops using the Three Horizons framework to create a visual system map which explored three overarching questions:

- What destroys trust?

- What builds trust?

- What should be scaled up to further build trust?

The detailed observations of the collective participants were captured on an online whiteboard which replicates the maps, images from which are below.

We worked with a talented student from the University of Westminster, Aloe Corry, who developed these images to capture the essence of the system maps which evolved over the course of the afternoon (see image on the right).

Group 1 was asked to use post-its, coloured card, paper, pens and glue to share their thoughts on the first question: What destroys trust?

Participants were then asked to share their thoughts on the group’s collective responses. They discussed the fact that lack of trust often starts long before involvement in the criminal justice system with lack of trust in the care system, education and health agencies cited as primary examples. This lack of trust is then transferable (i.e., the view that authority figures let you down) and is compounded by lack of understanding or confusion about these systems as well as the criminal justice system. Participants felt that the opaqueness of them creates alienation and pipelines to prison. People in the system described how they had felt dehumanised, labelled and ‘othered’ by their experiences from a young age and how these crushed and shaped their identities. Once in the system, the rigid conditions and stringent expectations of the criminal justice system (e.g. recall and breach of licence) and poor communication (e.g. about delays in court processes) reinforce this lack of trust. This feeds a perception that ‘no-one cares’ about people stuck in the system.

Participants spoke of a loss of trust within the police and prisons due to corruption which taints the reputation of the whole system. Prisons can also in themselves delegitimise the whole criminal system. The politicisation of criminal justice was similarly seen as destroying trust. Overall, there was a sense that relationships are so damaged by the system and within it, that it was a challenge to know where to start with repair and reconciliation (i.e., acknowledging harm, listening to communities affected and committing to reform). This sense of helplessness was extended to ongoing failure of actors and organisations within the system to engage with evidence, acknowledge what is not working, and implement recommendations. Scrutiny bodies, like Independent Office for Police Conduct, which could play a significant role in building trust, were not doing so.

Another element of discussion was the importance of looking upstream to prevent people both from becoming involved in the system and from getting further into it by thinking jointly about alternative routes to give people second chances. Nevertheless, participants believed that there were not sufficient resources for these types of activities e.g. once children are excluded from school, remanding to local authority accommodation. Failing to get to grips with this was seen as a huge cost to society.

Group 2 was asked to use the materials to add further thoughts to the responses to the first question and share their thoughts on the second question What builds trust? and the following sub-questions:

- When/where is trust built?

- Who/what builds trust?

- What should we stop doing to build trust?

Various features of existing criminal justice practice were seen as positive by the participants in the group discussion. They spoke of the power of peer-to-peer research, building on lived experience and providing a space where young people can just be listened to and be heard. More generally, participants were also positive about the greater policy focus on identifying and addressing the needs of young adults aged 18-25 from prevention to probation.

Participants also considered what makes people trust in the system, for example, the role of legal professionals who are able to effect changes through case law, the way judges give their verdicts, and the presence of an appeals system to question decisions. The principles of the rule of law and equality before the law should be tenets of trust but there was a sense that this is undermined by the adversarialism within a broader social system of social and economic inequality e,g. having sufficient resources to afford a lawyer following the reduction of legal aid. On the other hand, the system can itself play a role in building social and economic capital. Trust can also be built through strengthening the evidence base e.g. around what sentences are most effective at supporting people.

Another area participants considered was important in building trust was education and training for professionals working in the criminal justice system (e.g. in neurodivergence) as a means to help improve how people are treated within the system. This was seen as an essential element in promoting trustworthiness, alongside professionalisation. Initial contacts with services such as the police, court officials, judges can increase fear and mistrust as the justice system shames both victims and perpetrators which creates a vicious cycle of violence.

In some parts of the system there is some recognition that people commit crime who have been victims themselves, that the existing focus on negatives and failures is counterproductive, and that people need to develop new ideas about themselves and their capacities. Participants proposed that this should include more recognition that primary socialisation is important in preventing crime, including family and other social networks, and religion. Improvements in parts of policing in relation to violence against women and girls was also seen as necessary to promote safety and trust by women.

Group 3 were asked to build on both existing boards and to create responses for the third question What should be scaled up to further build trust? and the sub-questions:

- What should we start doing to build trust?.

- What role does/could the voluntary sector play in building trust?

- What could be learned /transferred from other areas of the system?

- Where are the opportunities?

- What could be done differently?

One of the key areas for improvement discussed by participants was the legitimacy of the system by acknowledging and meaningfully addressing known inequities to mitigate harms, for example, the experiences of black prisoners in terms of the disproportionate use of force and incapacitant spray, for example. in order to do so, the view was that relationships between criminal justice agencies and black communities require reconciliation which must stem from good motives and include responsibility and accountability of senior managers. There was potential to build on race activity by the College of Policing and National Police Chief’s Council but the importance of real change stemming from such activities cannot be underestimated. More specifically, there was a suggestion that police powers should be reviewed in consultation with the communities they serve.

There were calls for greater demonstration of how the system values the people involved in it. Examples of this were that staff training should show the value of professionalisation, with the example of 6-week prison officer training being seen as devaluing staff and the people held in prison, and that there should be greater intermediary support funded for victims and witnesses as well as scope for more reasonable adjustments to meet peoples’ needs. This included better data for understanding the system and the people in touch with it.

Strengthening scrutiny was another area seen as important, with scope for trust and legitimacy becoming more active elements of the work of scrutiny bodies. Scrutiny panels that observe policing incidents could look more broadly at organisational change, for example. On the other hand, greater recognition should be given to the potential for trust to be undermined by perpetual change.

Bolstering prevention and early intervention was a further theme of discussion with participants seeing scope for diverting more funding to community groups in recognition of the need for greater proximity of such groups to power and resources. Trust would be built when more services find the connections with the communities they serve and give them agency to address trauma where it is happening. It was suggested that voluntary sector organisation should be posing the question to statutory organisations ‘what are you doing to support this for us?. Others wished to see a greater role for both social services and, where possible, families safeguarding and supporting the needs of children and others who experience the criminal justice system second hand before they become involved in it themselves, rather than demonising them.

Participants proposed that restorative justice could be scaled up in various different ways, including creating restorative organisations, individuals, processes and cultures to foster fairness and respect. An example of cited was restorative circles between the police and young people, an approach which could be adopted in the mainstream were restorative principles included in police training.

Posters

Several participants presented posters for participants to view and discuss during breaks. Please click the images below to enlarge.

- Secondary analysis of data collected over a 20-year period by HM Inspectorate of Prisons, Royal Holloway University of London (Download PDF)

- Trials and tribulations: A par approach to African and Caribbean women with offending histories in understanding pathways to desistance using storytelling podcasting, Abigail Shaw, Birmingham City University

- The Rich Get Treatment, The Poor Get Prison: Contempt Of Court Imprisonment, Dr Rona Epstein, Coventry Law School (Download PDF)

Recommendations

Recommendations for change to improve trust in our criminal justice system and confidence in research

- There is a responsibility for everyone involved in the criminal justice system to understand and address mistrust by re-evaluating the power imbalances seemingly inherent within it, before it and beyond it.

- There is a need for honest conversations, politically and publicly, about how best to dealt with crimes that offend society.

- Prioritising access to services that should support people in touch with the criminal justice system would promote greater trust.

- There is scope for much greater application of restorative justice principles throughout the criminal justice system.

- There is a need for careful reflection on the question of ‘whose knowledge counts and how’ when criminological research is conducted.

- There is scope for much more research on victims and their experiences of victims throughout the criminal justice system, including in co-producing research studies and research questions.

- Criminal justice professionals should work with greater humility in their approaches towards individuals and communities who experience mistrust in the criminal justice system.

- Criminal justice agencies, like the Crown Prosecution Service, College of Policing, and the Sentencing Council, are recognising the importance of trust and should play a greater role in learning about what drives public confidence, as well as understanding and addressing the drivers of mistrust in the criminal justice system, particularly concerning gender and race.

- The tendency of criminal justice agencies to ‘protect the institution’ ultimately erodes trust. It is important that criminal justice leaders disconnect trust in individual criminal justice professionals from the trustworthiness of criminal justice institutions.